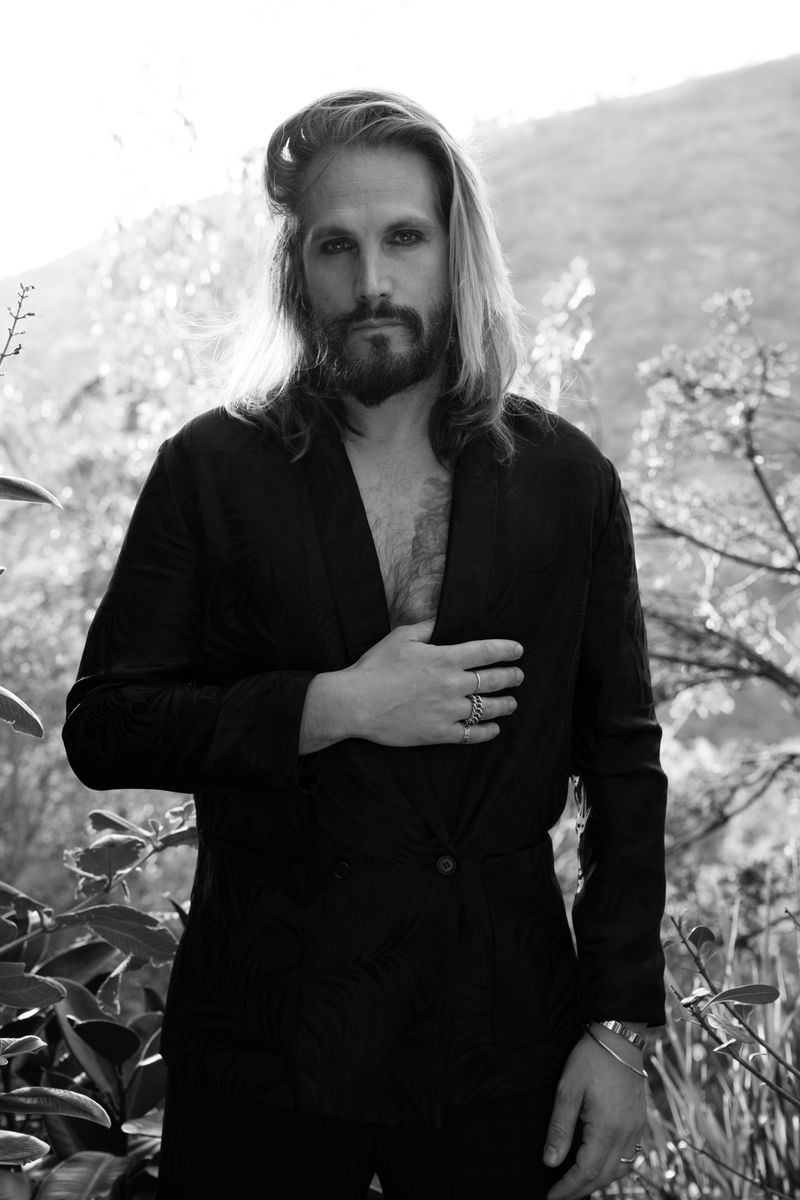

For his Venice Biennale debut within the Vatican Pavilion, filmmaker Marco Perego-Saldaña

entered one of the lagoon’s most concealed spaces: the Giudecca Women’s Prison.

For his Venice Biennale debut within the Vatican Pavilion, filmmaker Marco Perego-Saldaña

entered one of the lagoon’s most concealed spaces: the Giudecca Women’s Prison.

Portrait by Melodie McDaniel.

AIS:

What inspired you to choose the Giudecca Women's Prison as the setting for your pavilion piece at the Venice Biennale, and how does its history and the setting’s isolation influence the narrative?

MP:

Chiara Parisi and Bruno Racini [curated] this year for the pavilion. Chiara called me and said, “Do you want to be a part of the [Venice] Biennale and the Vatican Pavillion?” I said, “yes, that would be great.” And the Vatican this year chose to do a project inside a woman’s prison and the only request they had was to collaborate from a distance or very closely with an inmate. And Zoe and I – we were both invited to visit the women’s prison – Zoe is my partner in crime. And there, we decided to make [the] film together. When I went to New York to ask Alex [Dinelaris], who is [my] a mentor, writer and producer, what he thought [of the concept], he thought it was a great idea. So I flew to Venice and I interviewed some of the women. And we discussed a lot about freedom – what does freedom really mean?

[Within the prison] there’s some kind of community, where you can be free and be seen, [but] outside of the community, nobody can see you and you are completely invisible. And for these women --- there were two major points [I wanted to convey]: the resilience of these incredible women [as they endure] the cycle [of the prison system] and the question of freedom and what it’s worth.

When I was shooting the project inside, [I] shot everything in one take and in 2:39 [juxtaposed] by our approach outside where we shot everything in 4:3 [which feels very] small. The outside was very rigid and there’s a lot of cuts [purposefully]. Venice is one of the most beautiful cities in the world and it’s fascinating that these women are inside of this island and they clean the sheets and the bed of a very important hotel every Wednesday, but no one knows who these women are. I found it was important [to change that].

AIS:

[The film] gives them a bit of visibility which speaks to the title – it seems to unearth their hidden world.

MP:

Yeah - that’s what I'm really interested in – I’m interested in the introspective of a human being.

AIS:

The film depicts a profound exchange of objects between inmates, such as a sweater and lock of hair. What messages do you hope to convey through these exchanges?

MP:

When Alex wrote the scene about the sweater – the sweater is a sign of something very visceral, I find. It’s almost like giving your soul to each other. Or the exchange of the bracelet or the cigarette [represented] the idea of being together and sharing things [within] a community. When the women are together inside, they are noticed and responded to, but when they’re outside, these women are completely invisible.

AIS:

Religious imagery appears in the narrative; how did you decide to incorporate these elements, and what do they reveal about the women's sense of hope or spiritual connection within their circumstances?

MP:

I feel like when Zoe leaves behind the crucifix — I think that’s an important symbol. [The choice] to leave something behind — something that she doesn’t believe in anymore [is powerful]. And the images - I find it very interesting how Alex wrote in the second act [of the film]. [Traditionally], when you write the second act, for a character, [usually] everything is lost. In this circumstance, our character actually comes inside of the frame and [she’s emerging] everything is lost, but while another woman [appears]. It [reveals] the cycle - one after another and another. [The young woman] looks a bit like a young Zoe in a way and when she comes in, she doesn’t know anybody. [But] when she leaves, she has a sense of community. These women are so incredible that they’re capable of creating that type of community.

AIS:

Provided your experience interacting with the inmates, it’s clear that you have such a dignified approach to their portrayal - conveying the complexities, diversity and referencing their traumas, even touching upon intimate partner violence which is a challenging and sensitive matter to portray in film. How did you approach capturing the nuance of their backgrounds with such realism?

MP:

It was very difficult to go in and to ask someone to show a bit of who they are and [demonstrate] their vulnerability. I think what we did as a group, it was very important to have the entirety of them [in the film]. The best gift we ever had was at the end of the film, these women [not only] wanted to be seen, but they [actually] saw themselves. They were really proud of what they did there.

AIS:

The film seems to explore the idea that longing persists despite desperation. Was this a central theme for you, and how do you think the inmates’ encounters reflect human resilience?

MP:

I lived in [Giudecca] for almost ten days. Everyday that I was there it was incredible to see them – the community [of women]. I love the women of Giudecca, my wife loves the women of Giudecca. Every night we were getting letters or poems from them. I think we really have to [consider] the importance of second chances.

AIS:

The protagonist’s journey into the unknown and her act of collecting or choosing to leave behind personal items appear symbolic, illustrating the film’s central themes of memory, identity and transformation. What did you aim to communicate through her experience as she traverses the prison’s landscape and limits of the inmates’ reality into her future?

MP:

The majority of my work is about transformation of the soul – this is something that I connect to deeply in my work and my process. When you look through the corridor and you see all of these women and you look them in the eyes, you might finally try to look at them, but they’re really looking at you - wondering if there’s a sense of judgment or if you’re trying to understand their vulnerability. When you see their vulnerability, you need to take that in because it’s a gift – they’re not open to anybody, but they opened up to us – to me, Alex, Bruno, Chiara, Michael, Robb, to everybody and their willingness to [be vulnerable] really moved me.

AIS:

Your wife delivers a visceral and compelling performance as the film’s protagonist. What was your experience like directing your wife in this film and how did your dynamic influence your creative process?

MP:

I love my wife - she’s the best. She is the best part of myself, she is a true inspiration. I feel so blessed and grateful everyday that I learn from her. She has a raw vulnerability - she’s very earnest and that’s something that I admire about her very deeply. I really love it - I learn so much from her. I hope she learns from me some time, but really from my point of view, I feel so grateful to learn from somebody that is so raw and honest, [which is the trademark] of a true artist. She’s a big inspiration - she’s the best part of me, no doubt.

AIS:

The film’s distinctive tracking shot follows the inmates’ dynamic inner world. How did your choice in the film’s cinematic grammar lend to the narrative’s central themes?

MP:

Inside we used a very wide frame, 2:39 and we never cut the camera. When we were outside, we used a very small frame, 4:3 and we did a lot of cuts. Inside, we shot in black and white and outside, we shot in color, which provokes the question of what freedom is - is it outside or is it inside?

AIS:

As the director of a film that serves as timely social commentary, how do you see “Dovecote” functioning within the contemporary art and film landscape? In what ways do you hope it challenges the audience’s perspective on incarceration, community or hope?

MP:

It was very important to make a movie that was very honest. When we screened the movie in the United States, we met a woman that had been incarcerated for twenty five years and when she saw the film, she was moved [because] it represented her experience of community [within the prison], but when she walked outside, she felt invisible. For me, I didn’t make a movie for social commentary; I made a movie to talk about the character and if that character reflects something in the world, I feel that I’ve made something even more honest and that’s even more powerful.

AIS:

You’re currently in pre-production on your next project. You had mentioned that transformation is a central theme in your work - is this true for this next project? Can you share any details about who is attached to the film and what we can anticipate?

MP:

Yes - we’re in prep right now and we’re shooting here in Italy. I’m working with the same team — Michael [Cerenzie] and Alex Dinelaris on [this project]. It is very deep and profound – it follows the journey of a woman (played by Valeria Golino) who has lost her voice for over forty years and that no one can hear. I think I think it’s very important.