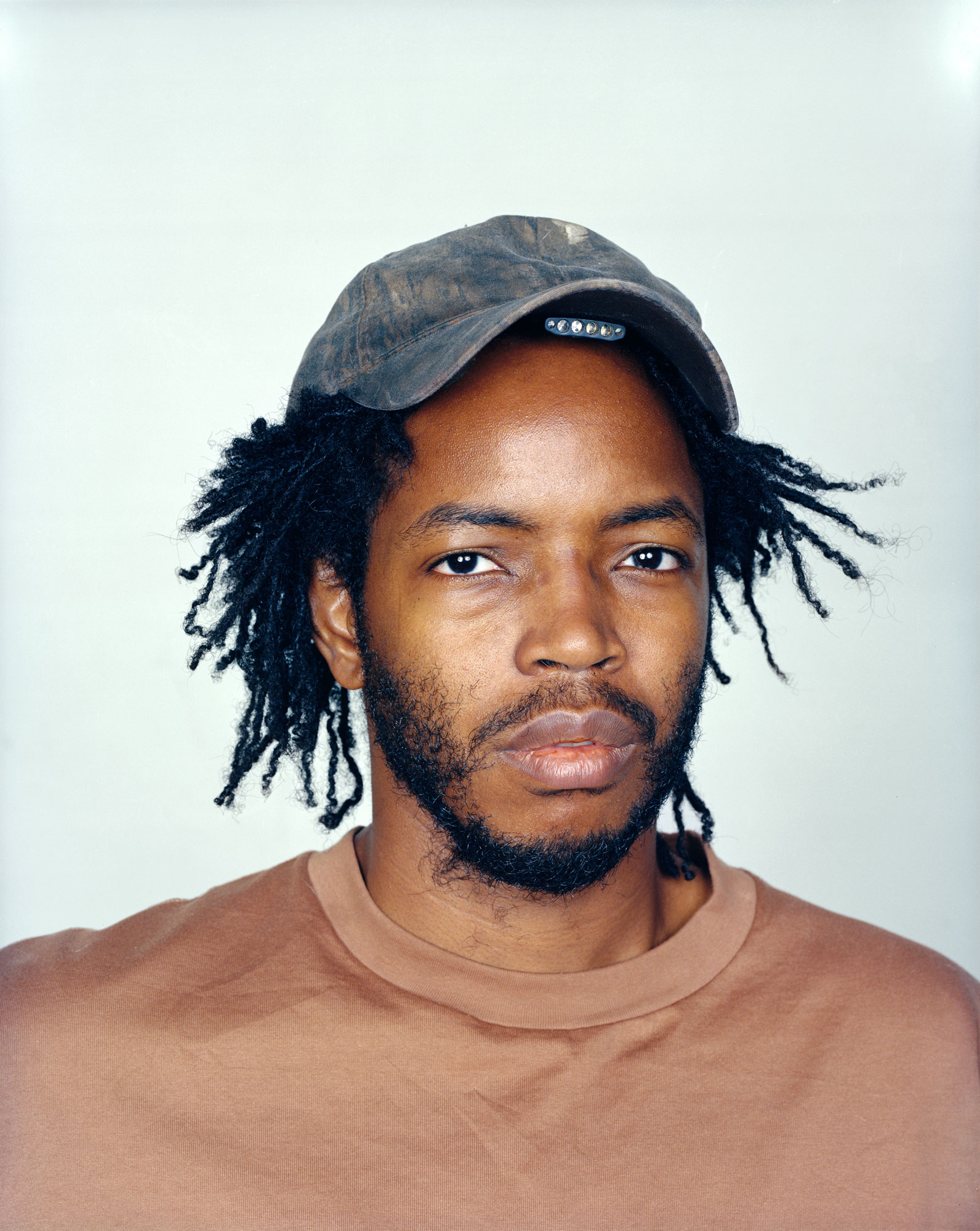

A FINE ARTIST OF DECONSTRUCTION

USES FAMILIAR OBJECTS TO CHALLENGE

OUR PERCEPTIONS OF OURSELVES

TEXT: STACEY GOERGEN

PHOTOGRAPHY: STEFAN RUIZ

A FINE ARTIST OF DECONSTRUCTION

USES FAMILIAR OBJECTS TO CHALLENGE

OUR PERCEPTIONS OF OURSELVES

TEXT: STACEY GOERGEN

PHOTOGRAPHY: STEFAN RUIZ

– b. 1983, Dallas

– MFA from Columbia

University

– Bachelor of architecture

from Cornell University

2023-2024

– Lisson Gallery, Los

Angeles

2021-2022

– Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

– Madison Square Park

– Brooklyn Bridge Park,

New York

2020

– Princeton University Art

Museum, New Jersey

– the Whitney Museum of

American Art

– Princeton University Art

Museum

– The Institute of

Contemporary Art, Miami

– The Studio Museum in

Harlem

– Sharjah Biennial 16

Sharjah, UAE, 6 February – 15 June 2025

– Hugh Hayden: Home Work, Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, September 18, 2024 – June 1, 2025

– A Garden of Promise and Dissent, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT, September 2024 – March 2025 (indoor)/September 2025 (outdoor). (group show)

Armor (2014)

Cherry bark on Burberry coat

91 × 81 × 30 cm

RAPUNZEL (2021)

In spite of these distractions, Hayden’s artwork, and his discipline toward his practice, are anything but disorderly. The African American artist was raised in a mixed-race neighborhood on the outskirts of Dallas where he attended a strict Jesuit high school. He went on to study architecture at Cornell University, which he practiced for almost ten years before earning an MFA from Columbia University. He worked 30-hours a week as a designer for Starbucks throughout his full-time graduate program. “What you’ve done as an undergrad is reflective of you as a person. I valued the rigorousness of the program,” he says of Cornell. “I always ask people where they went to college, because they had to be driven to get into certain schools, or their parents pushed them, but they don’t lose that rigor.”

His diligence paid off, and he has been widely recognized over the past few years. The Princeton University Art Museum presented Creation Myths at their Bainbridge House location in 2020; the same year, he completed a residency at Anderson Ranch. He installed two shows at the Lisson Gallery in New York. He also opened a solo exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art Miami and public art installations, ‘Huff and a Puff,’ at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in 2023 and ‘Brier Patch,’ at the Madison Square Park Conservancy in New York.

Perhaps Hayden’s focus on hard work is related to his interest in cultural notions of the American Dream – how it is defined, who has access and who does not, the different possible paths to its achievement, and what is lost in the process – which he often explores. Transforming ordinary, recognizable objects such as tables, chairs, and desks by carving them with spikes and pointy projections, he makes them almost menacing while still physically alluring. “All of my work has an element of the American Dream,” he says. “There is a seductive part, a part you want to touch, but at the same time there’s something scary or sharp and you don’t want to touch.” Raising questions about identity and belonging, Hayden confronts the disparities within the dream.

Hayden is known for working with all varieties of wood, usually reclaimed and sourced for its relevance to a specific project. He is focused on the handcrafted process, sometimes spending months on a piece. His early work explored identity through camouflage, and one piece, Zelig (2013), hangs on his studio wall. At first glance, it appears to be a log affixed to tree bark, but the surface is actually made of peacock feathers that have been painstakingly plucked with tweezers and then glued to blend into the bark. The title itself is derived from a Woody Allen film about a man in the 1920s who transforms himself mentally and physically into those around him. “I was interested in camouflage as a metaphor for trying to blend in or assimilate with society,” says Hayden. “This idea of camouflaging oneself on the surface to the American Dream.”

From exploring external differences, Hayden moved on to what makes people almost indistinguishable from each other, by sculpting bones and skeletons, stripping individuals of everything that makes them outwardly identifiable. “A doctor can tell someone’s ethnicity and gender from below the surface, but most people cannot,” he says. “For me a skeleton has no identity.” Pursuing this theme, he has made a large-scale sculpture of a skeleton for his ICA Miami exhibition called Roots (2021). The skeleton, bifurcated with branches, is made from bald cypress, a tree native to his mother’s home state of Louisiana which he visited frequently growing up.

Hayden’s installation at Madison Square Park includes 100 elementary school desks arranged in rows, each seat and table exploding with elaborately entwined branches pushing up and out into a tangle. “I think the most common way of looking at [the desks] is that you are the viewer and they are off limits.” He observes, “But the alternative perspective is that someone has actively put a deterrent to keep you away. Either way, no one can use them.” The piece, called Brier Patch, suggests a place that can be simultaneously safe and dangerous, depending on who you are and what it means to you. Although he wasn’t specifically thinking about Covid-19 school issues, he admits that others have interpreted it as such. “The more I grow as an artist,” he says, “the more open I am to the way you come into the work because people can see things in different ways.”

Ideas of interdependence and community also run through Hayden’s practice, and are most clearly seen in the intricately staged dinner parties that he began hosting in college. One culinary installation (as he now calls them) included a 12-foot-long picnic table that he placed on a rocking chair base. The guests, all in uniform, had to work together while eating to keep the table stable so the food didn’t tip off. At one level it was fun, but also nerve wracking and uncomfortable, forcing the guests to be dependent on each other. Like his sculptures, these events are about “society and trying to blend in, a manifestation of working together to see what the implications are for the larger group.”

In fact, many of Hayden’s works reference interdependence and community either directly or indirectly. Talented and Gifted/Passing (2021), is a sculpture of two school desks made from Gabon Ebony. One desk made of black heartwood leans into the other, which is light sapwood, appearing to push it backwards. “The culinary installations are participatory,” he says, “but so are the desks, as neither can stand without the other. There is an interdependency and the implication of a group.”

Hayden had his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, at the Lisson Gallery, presenting a new series of installations that explore “the prosthetics of power.” Using the organic materials he is known for, he delves deeper into topics of revelation, intimacy, desire, and sexuality.

Exploring what it means to assimilate, conform, and succeed in America, the artist acknowledges our similarities and differences while exploring the ways in which race and ethnicity impact our paths. And, in spite of exposing historic inequality and institutional barriers, he still believes that “there is an innate American desire to believe in the notion that success is possible for everyone.”