Shirin Neshat_002

Shirin Neshat_003

Shirin Neshat_004

Shirin Neshat_005

A lioness of esoterica embraces narrative filmmaking to amplify her voice for a region in the throes of revolution.

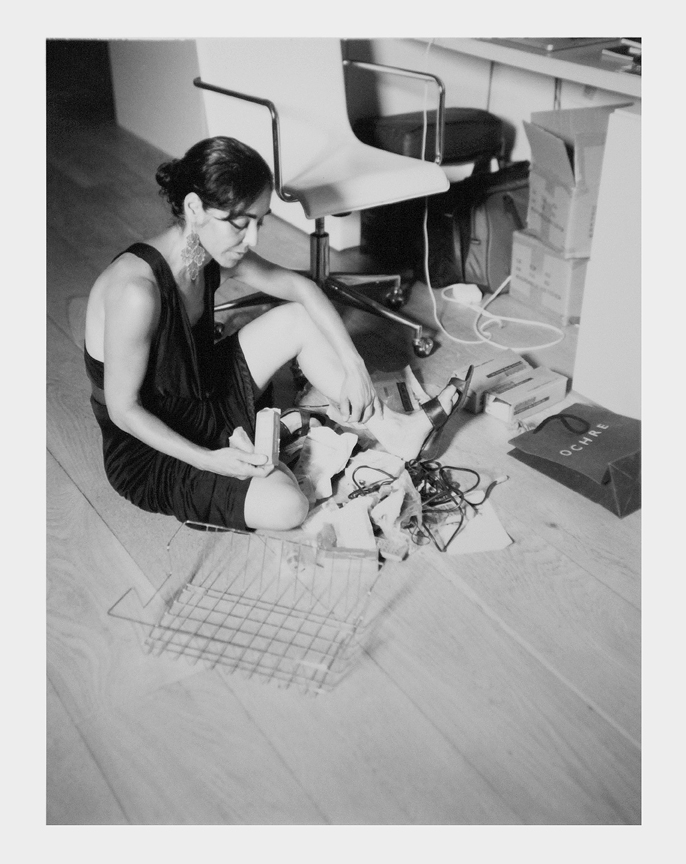

Interviewed by Ike Ude / Photographed by George Pitts

The Iranian born, New York City based Shirin Neshat is a most resilient visual artist whose evolution in the film medium is astounding.

Mostly known previously for her video art, a relatively esoteric genre, Women Without Men, her first feature film meant for a larger public, turned out so excellently that it earned her the Silver Lion for best director at the 66th Venice Film Festival. A heroine for the much-polarized nation of Iran, a bridge between the West and Middle East, a visionary in making the impossible, possible, I recently had the pleasure to interview her for Aleim. I’ve always fancied her as the real Persian Lioness, one of my heroines.

1. Congratulations on your award-wining film, Women without Men. Strictly speaking, is this your first non-art film—in the sense that it is not made for a smaller, elite art audience?

Absolutely, in fact I remember it was exactly after Documenta of 2002, that I felt a sort of exhaustion from the art world and found an urge to take time off to contemplate on a new direction for my art. That new direction was my long time seduction and love affair with cinema. From the beginning though I knew if I would make a long film, it would be for the general public and not exclusive to the art audience. Of course this task was easier said than done, since I didn’t have the necessary experience or the skills to make a commercial film. I had never studied filmmaking; I had enjoyed a great artistic freedom making my short videos, in terms of allowing myself to be as evasive, abstract and fragmented as I wished. But once dealing with the mass public who is seated in cinema for more than one hour and half hours, I now understood that the languages and rules of visual art and cinema are radically different. And therefore to communicate to an audience who is not interested in ‘conceptual art’ but a ‘story’ that they might absorb in a film, means a deep respect and understanding of the elements in filmmaking. This included character study, narrative comprehension, new idea of pacing, all of which I had no previous experience with. So it was not enough to be simply radical against my own field, but to be bold to be a student again and to educate myself in a entirely new language.

2. Well said. What is one supposed to read into such a title, “Women without Men?” Please explain.

The title comes from the novel of “Women Without Men” which was written by Iranian woman author Shahrnush Parsipur. The writer’s explanation is similar to mine, that the narrative is not about women ‘against’ men rather women who could not cope with ‘men.’ She also explains her choice of the title as a response to Ernst Hemingway book called “Men Without Women!!”

Personally, although our re-adaptation of the book radically changed many aspects of the original story; I felt this notion of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ was very present, not only through pursuit of women’s lives but through other allegorical ideas such as the ‘orchard.’ For me the orchard became a feminine space where one became temporarily free of the outside world, its violence and the reality it came with. While the city of Tehran became a masculine space, representing history, socio-political realities of a country.

Ultimately what I really wished the audience to take away from this film was its poetry of linking the crisis of these four women and the crisis of the country together; to understand how indeed both the women and the country were looking for the same thing, an idea of ‘freedom,’ ‘independence,’ and ‘democracy.’

3. It is a politically charged film. What are your objectives and hopes with this film?

I chose to expand the political dimension of the story, as in the novel the author only hints to the period as a background to the women’s stories. Summer of 1953 is a pivotal moment in Iranian political history. It is when the American CIA with the help of the British government overthrew the Iranian democratic government of our beloved Prime Minister, Dr. Mossadegh through a coup de’tat and re-installed the Shah. This period later became the foundation for the break down of the relationship between the USA and Iran; the spread of fundamentalism; and of course it led to the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979. Most Americans and British public today are entirely ignorant of this very significant point of history and their own country’s history in over throwing democracy in foreign countries.

So this film becomes somewhat educational and in a fictional way returns to this period, not only to point toward this important political event; but also to offer another perspective on the Iranian culture prior to the Islamic Revolution. Today, unfortunately the world seems to remember us only as an Islamic state; and has no recollection on Iran as a progressive, modern, secular and cosmopolitan society.

4. So far, have some of these hopes and objectives been met?

When I look back, I would say this film is not flawless, but it’s an original attempt in pioneering a new way of story telling in cinema. The book was also extremely complicated to re-adapt so overall, and it was tough to balance visual art and cinema, magic and realism etc. So I would say it has not been an easy project, but the film has succeeded beyond my expectation in terms of visibility. It has really found its place and audience in the film world; and most importantly it has reached the general public, as it is being distributed in regular cinemas in almost every territory in the world. Some of the public have little to no familiarity with my art work. In particular I feel like I have gained a large audience among the Iranian community, most of them rarely enter a gallery or a museum but certainly go to see films. This film is banned in Iran, yet the dvd has been distributed in the black market and many Iranians all over the country have seen it. This gives me a great pleasure

5. With the ban of your movie in Iran, one supposes that you, as individual are also banned from coming into the country. Are you thus having Salman Rushdie moments, in other words, is your life in any particular danger from the Iranian Islamic Republic power elite and do you need special security details in order to get around?

I have not been able to go back to Iran since 1996, so this is not something new. But what happened since past summer of 2009 is that ever since the Green movement developed in Iran, for the first time, I became more politically active and vocal in support and solidarity with the students and against the government’s fraud election. My friends and I then went on to wear green in our premier in Venice film festivals, which got a huge media attention, and I gave many interviews. So since then I have been black listed and have been called names such as the ‘Zionist agent’!! But I’m not really in danger like Salman Rushdie was at one moment; or I am not that particular to the government as thousands of artists have put themselves and their families at the same or worst risks by being vocal.

I should explain that today, as an Iranian artist, it is difficult and almost irresponsible to remain neutral and non-political to the atrocious behavior of the Iranian government. And this proximity to the question of politics has displaced artists in exile such as myself, and huge problems of harassment, arrest, torture, for those artists who live in Iran. At the same time the very fact that artists, any people of imagination are posing a ‘threat’ to the government, by provoking the public, it has empowered us nationally and internationally. Now we know that our voices are being heard, and our art are being watched.

6. Returning back to the movie, how long did it take you to complete this film?

The process proved to be very long, nearly 7 years! In January of 2003, I went to the Sundance Film Institute’s writer’s lab in Utah for an intense work on the script. In 2005, we shot only the story of Zarin, one of the key characters in Marrakesh. In 2007 we finished the script and returned to Casablanca to shoot the entire film. Then finally it took between 2007 to 2009 to complete the post-production work and the film was finally premiered at Venice Film Festival in August of 2009. And since then to date; we have been traveling with the film for festivals and distribution of the film in various countries.

7.Can you share with us some of the trials and tribulations that you went through in order to get this film finally finished and released to the world at large? I could say that every stage of the process was both exhilarating and painful. I can only compare this experience with the process of child bearing and child birth!! First of all because the producers were based in Berlin, I had to literally divide my time between NY and Berlin for many years and devote my personal life to the project. The script writing process was very complicated, mainly because I had no experience with writing before and it took about 200 versions to arrive at the final one. Later there were problems with fundraising, since a European company was trying to find support for a film by an Iranian-American director shooting in Morocco, so as you can imagine it was not easy.

The eight weeks of shoot was not easy as it proved to be a true test of my stamina both physically and emotionally; but perhaps most tasking was the post-production stage. Once on the editing table, we discovered that we literally had to get rid of our script and put the puzzle together in an entirely new way. It was extremely tedious to find the right balance in between art/cinema, magic/realism, and the allegorical/political content, all within a narrative that followed simultaneously 4 main characters’ journeys and a country in turmoil. So after working with number of different editors and creating about endless versions of the film, we arrived at what you see today. Now the child that I and many others worked so hard to nurture is born and has a life of its own but at least we can say: “we gave it our best.’

8. Great movies and worthy artistic endeavors often require tremendous patience, time, money/credit. It is wonderful that it came to fruition and a successful one at that! What is your state of mind at this particular moment?

I have fallen in love with cinema; both as an artistic medium and as a form, which is truly grass root. Generally, I find there is more ‘democracy’ in filmmaking than in visual arts. Visual arts serves a very educated, elite class who absolutely must be informed about history of art in order to appreciate any form of art. But cinema comes from the primitive tradition of ‘storytelling’ and it does not require an education of film history.

Also, I do feel certain amount of frustration with the notion of visual artist as ‘commodity’ makers; whose objects ultimately end up in museums or wealthy collectors’ homes. I have no problem with wonderful collections and feel proud to be in them, but the activist in me resists the idea of entirely operating within this exclusive world. I have always dreamt of making art that comes closer and is more accessible to the general public.

Having said all above, of course filmmaking is also a commercial enterprise and depends heavily on the market and the box office. But then the artist must be creative in how to make a film that is both marketable and meaningful.

This finally brings me to the last point, which is about the form. With filmmaking, I believe I am making photographs, sculptures, painting, choreography, making music as well as telling a story. I believe cinema is inclusive of all the artistic elements that I am interested in. So now I’m thinking about how to develop films that are truly commercial, yet artistic and complex.

9. Yes, the film medium marries all the art forms. Now, are you considering doing other movie projects now that your very first foray in this arena met with such astonishing success?

I am a very restless artist. Over the years, I keep finding myself indulging in projects that are super challenging and demand that I reinvent myself; as if I need to test and question my own artistic capabilities. I need the excitement artistically otherwise, I feel ‘dead.’

Recently, I’ve optioned another book for a potential next movie, which is called “The Palace of Dreams” by an Albanian author, Ismail Kadare. This summer I’m working on the treatment. Also, l’ve been contemplating on a film about Oum Koulsoum, the most significant Arabic singer of the 20th century who happened to be a woman and died in mid 70’s. I’ve been researching and reading a lot about her and constantly listening to her music. So I am not sure which one will come first.

In addition, I have shot new photos, which I’m working on. These photos are black and while photographs which will have nothing to do with cinema. So now you can see after seven years of working on the same project, I am so hungry to work on new projects.

10. Will your next movie be along a similar subject matter and style of filmmaking?

“The Palace of Dreams” is a surrealistic narrative just like “Women Without Men.” It could be an extremely visual and allegorical film. It goes in between politics, religion and poetry. Just my way of making films, but oddly there is only one female character, it’s all about men. It is a story about an institution called the ‘palace of dreams,’ which on daily basis receives people’s dreams from all over the country. The dreams go through the process of reception, selection and interpretation. The purpose being that the state believes God sends his messages through dreams and therefore, they are looking for signs of various catastrophes etc. It’s a fascinating and absurd tale of religious fanaticism, political ideology, oppression, yet with graceful and full of humanity and poetry.

The Oum Koulsoum film would be a biography but one that would have to be done not in the conventional form of biography but highly fictionalized. I’m really thinking about this one, since this would be an entirely new direction for my work.

11. Hitchcock always maintained that he never cared for content as such. How important is content and/or narrative to you?

I have no problem with ‘entertainment,’ which is quite an important part of any cultural activity; but art must also function beyond that. Art must inspire, and help us think and reflect in new ways. I don’t however like didacticism in any form of art. I have never desired to deliver an important messages or create a profound revelation for the people through my work, rather I am satisfied if my work simply touches the audience in the degree that they might have a moment of reflection. Unfortunately, in this age of technology, we are facing an audience who has short attention span, and expects fast results. So it is extra challenging for filmmakers who are trying to make an offering that might be a little more layered and complex than usual. Not everyone is as good as Hitchcock!

12. How do you then rate most of the Hollywood movies based on their messages or lack thereof?

There are plenty of Hollywood films and directors that I admire. In fact some of my most favorite films today are Hollywood films; such as “The Thin Red Line” by Terrance Malick, “Blade Runner” by Ridley Scott, and “There will be Blood” by Paul Thomas Anderson. Directors like David Lynch, Tim Burton, Robert Altman, Stanely Kubrick, Jim Jarmusch and many more have redefined Hollywood and there is a great audience for what they make. Every one of these directors has injected some sort of content that in my opinion makes their stories transcend pure entertainment. This does not mean that they are sending important ‘messages’ but they are provoking the public enough so when they leave the cinemas, they continue to think about their films.

This is lacking entirely from other types of Hollywood films, which have a purely commercial and superficial function, so when the audience leaves the cinemas, they immediately forget the film. To give you an example, I can think of a latest offering the film called “Inception,” which pretended to be complex; but in my opinion it was only an ‘action’ movie and once you left the theatre all you remembered were a few expensive and beautiful apocalyptic shots!

In Europe you have another reality, where there is a larger audience for non-commercial, independent films. If classic directors like Andrei Tarkovsky, Abbas Kiarostami and even more recent ones like Lars Van Trier, Roy Anderson are hardly known and appreciated in the USA; there is a large following for them in Europe. So I suppose the diversity in between American versus European culture and audience also speaks truth about what is produced to feed the public’s expectation.

13. Is there such a thing as a characteristic Iranian film sensibility in much the same way as say, the French New Wave or even Indian Bollywood?

For more than two decades Iranian cinema enjoyed a sort of renaissance; as they surprised the world and made fantastic films under extreme censorship and no financial support. The stories almost always stayed within the sociological framework, which quietly yet subversively reported on life under repression in Iran. Most of the times since no sex or violence could be portrayed, the films focused on the subject of children and before we knew, hundreds of such films were being made in this style almost exclusively for the international film festivals. The best and most successful masters of such films were Abbas Kiarostami, Jafar Panahi and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. But several years later, a tired audience and festivals turned their attention away from Iran and such films, so the Iranian filmmakers had to rethink and redefine their directions.

What is developing in Iran today; is a new generation of filmmakers who are no longer focusing on the subject of ‘deprived’ children, rather the middle class youth. These new talents are making very interesting films both sociologically and artistically that are not exclusively screened in international film festivals but also screened in movie theatres for the Iranian public in Iran. Among such innovators are are Asghar Farhadi who made “All About Ellie,” and the continuing talent Abbas Kiarostami who keeps reinventing himself.

14. Does Women without Men owe a debt to the Iranian film sensibility or is it simply your own individual approach to film making?

I would say that “Women Without Men” does not really follow the footsteps of Iranian cinema. First of all, the Iranian films are mostly made in a style that is commonly known as ‘docu-drama,’ meaning that they always rely on sociological realism to tell their stories. WWM is a surrealistic narrative, with a foot in magic and another foot in history and realism. Also important to point out that almost all Iranian films are covering Iran after the Islamic revolution (1979,) WWM takes place in 1953, and is one of the only fictional–historical films I know that covers Iran before the revolution.

Another big distinction between my film and other Iranian films is how WWM relies on visual aesthetic of my past work and language to tell its story; which is certainly a hybrid of Persian poetry and conceptual art that I’ve been learnt in the West. Therefore WWM is by no means a ‘pure’ Iranian film, rather what I would consider an Iranian film with an ‘accent,’ polluted by Western influences while with a story that is Iranian.

15. What extra bonus question would you have liked to have been asked?

I feel you have covered a very good arena of questions. I can’t think of any more.